Our President, Professor Tom Bourne, considers the psychological impact of baby loss: Baby loss is often a taboo subject. It is estimated, that 23 million miscarriage take place every year worldwide with 44 couples losing their pregnancy every minute. For Baby Loss Awareness 2021, ISUOG is asking our community to recognise the psychological impact and extend their care beyond “diagnosis and treatment” for couples experiencing baby loss

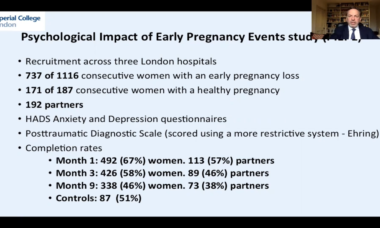

It has been estimated that worldwide about 23 million miscarriages take place each year. This equates to 44 couples losing their pregnancy every minute . Think about those numbers for a moment. For many women it will be the most traumatic event in their life. The psychological consequences include anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. We know from our research that the loss of a longed-for child can leave a lasting legacy, and result in a woman still suffering post-traumatic stress nearly a year after her pregnancy loss . We also know that partners are impacted significantly and that there is an increased likelihood of relationship breakdown.

Women may wrongly feel guilt or failure about the loss, and so stay silent.

It is important that people are encouraged to share their experiences and so break the taboo that exists in relation to talking about early pregnancy loss. It is also very important that employers understand the impact of early pregnancy loss on women and the potential for posttraumatic stress. This means that miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy become issues that are discussed more openly both in society and the workplace. Women after an early pregnancy loss who have posttraumatic stress will often find it hard to work and need the support of employers. Policy makers should pay attention to this issue and mandate that this support is essential.

Current care following an early pregnancy loss is variable. However in general most women and their partners receive no formal psychological support. Many will benefit from the excellent information provided by patient support groups such as Tommy's the miscarriage association or ectopic pregnancy trust , however women with post-traumatic stress symptoms need to be assessed by a psychologist and receive appropriate treatment probably based on trauma focussed cognitive behavioural therapy. It seems likely that in future women will be screened for significant psychological pathology at about 3 months after a loss. Trials are currently taking place to determine the optimal treatment for posttraumatic stress specifically associated with pregnancy loss.

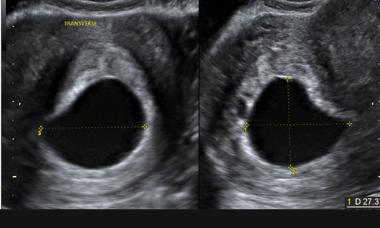

It would seem axiomatic that how women are cared for when they have a pregnancy loss is important. Currently there is seems to be a lack of understanding that the impact of losing a baby is not necessarily gestation dependant. Irrespective of gestation all pregnancies deserve the same level of competence from those examining them, the same robust diagnostic criteria and the same care and compassion. A number of practical measures would help such as ensuring access to good quality clinical care. Ultrasound assessment should be available at times that suit women (e.g. at the weekends), for women who opt for surgery this needs to be carried out promptly without delays or being pushed into emergency operating lists, staff must be properly trained and supervised. Conversely the wellbeing of staff working in early pregnancy is an important and often overlooked factor.

We recently published a paper that showed over 40% of trainee doctors working in gynaecology suffer from burnout . This is associated with a lack of empathy and compassion. We need to ensure staff are well enough to care for people properly. Being trained in how to break bad news, compassion and providing an appropriate environment where women can be seen matters. Similarly for outpatient management of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy, giving realistic expectations of what to expect is crucial. For many expectant management although effective may not be the best option psychologically.

Culturally (in the UK at least) in general people do not talk about miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy. For example if we consider the “12 week rule” whereby women and their partners in general do not inform people that that they are pregnant until they are around 12 weeks has meant that many women suffer a loss without their friends or family knowing anything about it. The result being there is a lack of support for the individual and a lack of understanding of the impact of the loss more generally. A further result of early pregnancy loss not being discussed is that partners, friends and colleagues are in many cases unaware of the serious psychological consequences – and so do not recognise the symptoms of for example PTSD – and so are not in a position to help those effected access appropriate treatment and support. Recently there has been a move to encourage people to “talk about miscarriage” – which we as clinicians should strongly support.

Finally women may wrongly feel guilt or failure about the loss, and so stay silent. The nomenclature still used in relation to pregnancy loss does not help as it is wedded to the notion of failure, unintentionally attributing blame: “failed pregnancy”, “incompetent cervix”, “missed abortion”, “retained products of conception”, and “blighted ovum” often make women feel as if they have failed. The language that we use in this area really matters and must change. Katy Lindeman wrote an excellent article in the Guardian where she simply requested, “please doctor don’t call my baby a “product of conception ”. Still papers are published where miscarriage is called spontaneous abortion. Journals such as Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology should in my view adopt appropriate language as part of their editorial policy.

It is it important that it is understood that for many women and their partners, miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy will be the most traumatic event that has happened in their lives up to that point – and will create a lasting legacy. Many will experience psychological distress that will persist for years if untreated. Having a greater appreciation of this hopefully will enable friends, colleagues, employers and family members to better support women and their partners going through a pregnancy loss. As clinicians we need to understand that the care of couples suffering from early pregnancy loss extends beyond “diagnosis and treatment” and must include psychological support for those who need it. Baby loss awareness week is an important moment in the year to reflect on these issues and ask ourselves how we can improve our care both individually, but also as a profession.

Resources on Pregnancy loss from UOG Journal

Psychological impact of early miscarriage and client satisfaction with treatment: comparison between expectant management and misoprostol treatment in a randomized controlled trial, by Fernlund and colleagues

Pregnancy Loss resources on ISUOG.org

The psychological impact of early pregnancy loss

Prof. Tom Bourne

New research highlights need for comprehensive reform of miscarriage care and treatment worldwide to replace fragmented approach

The Miscarriage Matters report found that existing care for sporadic or recurrent miscarriage is inconsistent and poorly organized worldwide, and a new system is needed to ensure miscarriages are given a high priority and women are given the physical and mental healthcare they need.